The 1918 Influenza Pandemic, often called the Spanish Flu, stands as one of the deadliest natural disasters in modern history. Emerging during the final stages of World War I, this devastating pandemic infected about one-third of the world’s population and caused tens of millions of deaths worldwide. Unlike typical influenza outbreaks, the 1918 pandemic exhibited unusual patterns of mortality and spread, resulting in profound social, economic, and medical consequences that still resonate today. This article explores the origins, characteristics, impact, and legacy of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, shedding light on how this catastrophe shaped the future of global public health.

Origins and Early Spread: The Unseen Enemy Emerges

The origins of the 1918 influenza virus remain a topic of research and debate. The virus is believed to have been an H1N1 strain of the influenza A virus, but pinpointing its exact geographical source is difficult. Some studies suggest the first cases may have appeared in the United States, possibly in a military training camp in Kansas, before spreading to Europe with American troops. Other hypotheses point to France, China, or even other locations as the point of origin.

What is certain is that the global conditions during World War I created a perfect storm for the virus to spread rapidly. Troop movements across continents, cramped living conditions in military barracks and trenches, and disrupted sanitation systems allowed the virus to travel swiftly and mutate.

Spain, a neutral country in the war, was among the first to report the outbreak openly. Due to wartime censorship, many combatant countries suppressed news of the illness to maintain morale, leading to the pandemic being dubbed the “Spanish Flu,” despite Spain not being the origin.

The Virus and Its Unusual Characteristics

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic was highly virulent and had some unusual epidemiological characteristics:

- Unusually High Mortality in Young Adults: Unlike typical influenza viruses that predominantly threaten the very young, elderly, or immunocompromised, the 1918 strain disproportionately killed healthy young adults aged 20 to 40. This anomaly baffled scientists and amplified social and economic impacts.

- Rapid Onset and Severe Symptoms: Patients often developed sudden high fever, severe fatigue, and acute respiratory distress. Many died within days from pneumonia caused by the virus or secondary bacterial infections.

- Immune System Overreaction (Cytokine Storm): It is now believed that the virus triggered an overactive immune response, where the body’s defenses caused widespread inflammation and lung damage, leading to respiratory failure.

- Multiple Waves: The pandemic struck in three waves over roughly 18 months, with the second wave in late 1918 being the most deadly.

The Three Waves of the Pandemic

The 1918 flu pandemic unfolded in three major waves:

- First Wave (Spring 1918): This wave was relatively mild, resembling typical seasonal influenza. It infected many but resulted in fewer deaths, serving as a warning of the more severe outbreaks to come.

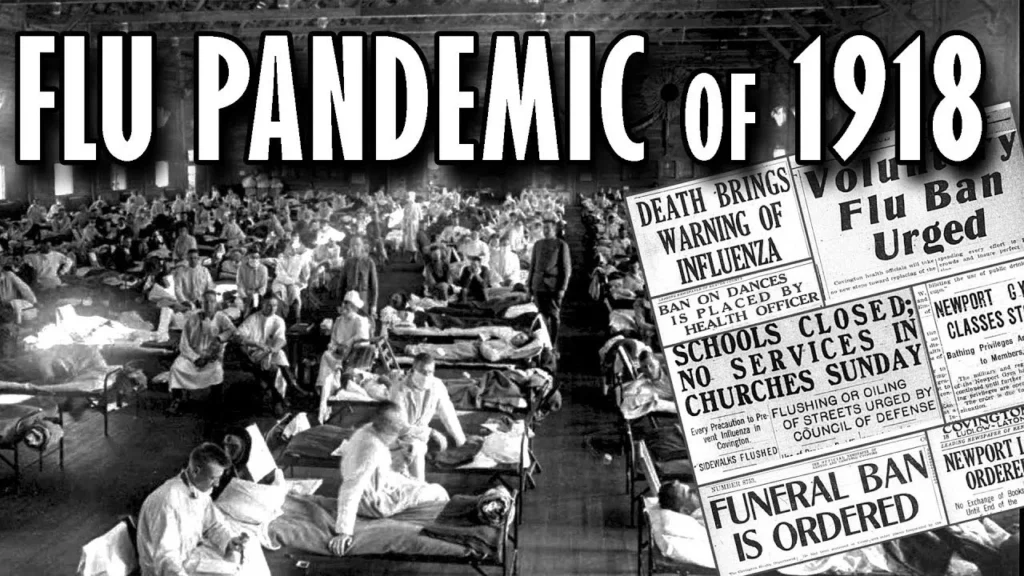

- Second Wave (Fall 1918): The deadliest and most virulent phase. The virus had mutated into a more lethal form. It spread rapidly and caused unprecedented mortality. Hospitals were overwhelmed, and social services struggled to cope. Death tolls peaked during this wave.

- Third Wave (Winter 1918-1919): This wave was less severe than the second but still caused significant illness and death in many regions before gradually fading away.

Global Impact: A Pandemic Without Borders

The 1918 influenza pandemic was truly global, affecting nearly every country and continent. An estimated 500 million people, roughly one-third of the global population, became infected. Death toll estimates vary widely, but most scholars agree that between 50 million and 100 million people died worldwide.

- Disproportionate Impact on Indigenous and Isolated Communities: Remote populations, such as the Inuit in Alaska, Aboriginal Australians, and Pacific Islanders, suffered mortality rates as high as 90% in some cases due to lack of prior exposure and limited healthcare.

- Urban Centers Hit Hard: Cities with dense populations and poor sanitation experienced rapid spread and high fatalities. Philadelphia’s famous Liberty Loan parade in September 1918, held despite warnings, contributed to a catastrophic spike in cases and deaths.

- Economic Consequences: The pandemic caused labor shortages, reduced production, and strained economies recovering from the war. Businesses closed, and the workforce was decimated, especially since many young adults were affected.

- Healthcare Crisis: Medical infrastructure was overwhelmed. Hospitals faced shortages of beds, staff, and supplies. Many doctors and nurses contracted the virus themselves, reducing available care.

Social and Cultural Effects

The 1918 pandemic profoundly affected societies:

- Public Behavior and Fear: Fear of contagion led to the closure of schools, theaters, churches, and public places. Mask mandates and quarantines became common. People isolated themselves, disrupting normal social interaction.

- Psychological Impact: Widespread grief and trauma resulted from the loss of family members and friends. The pandemic exacerbated the sense of uncertainty already prevalent due to World War I.

- Impact on Families: The death of young adults created social and economic hardships for families, many of whom lost their primary breadwinners.

- Misinformation and Stigma: As with many pandemics, misinformation circulated, and some communities faced stigma or blame for spreading the virus.

Medical and Scientific Response

Despite limited knowledge of viruses at the time (influenza virus itself was not isolated until 1933), the 1918 pandemic prompted advances in medical science and public health:

- Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions: Public health officials implemented measures such as social distancing, quarantine, school closures, and mask mandates. Their effectiveness varied based on timing and public compliance.

- Growth of Public Health Infrastructure: The pandemic highlighted the need for organized public health systems, leading to the establishment or strengthening of health departments in many countries.

- Vaccine and Research Initiatives: While no vaccine was available during the pandemic, research into influenza intensified, eventually enabling vaccine development decades later.

- International Cooperation: The global scale of the pandemic underscored the need for international communication and cooperation in disease surveillance and response.

Legacy and Lessons for Future Pandemics

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic left a lasting legacy in medicine and public health:

- Importance of Preparedness: The pandemic exposed vulnerabilities and underscored the need for pandemic preparedness plans, including stockpiling medical supplies and developing rapid response protocols.

- Value of Early Intervention: Data showed that cities which implemented social distancing early experienced lower mortality rates.

- Need for Clear Communication: Transparent and consistent public messaging helps combat misinformation and promotes compliance with health measures.

- Investment in Science and Healthcare: The crisis accelerated influenza research and highlighted the importance of strong healthcare systems.

- Global Collaboration: The pandemic demonstrated that infectious diseases do not respect borders, emphasizing the necessity of international cooperation.

These lessons have informed responses to later pandemics, including the 2009 H1N1 outbreak and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic remains a stark reminder of the devastating power of infectious diseases. It claimed millions of lives, disrupted societies, and challenged medical science. Yet it also catalyzed important advancements in public health and medicine that continue to protect humanity. Remembering this global tragedy helps ensure that future generations are better prepared to face similar threats with resilience and knowledge.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the 1918 flu called the “Spanish Flu” if it didn’t start in Spain?

A1: Spain was neutral during World War I and did not censor news of the outbreak, unlike combatant countries. This made Spain appear to be the epicenter, even though the virus likely originated elsewhere.

Q2: How many people died during the 1918 influenza pandemic?

A2: Estimates vary from 50 million to 100 million deaths worldwide, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in history.

Q3: What made the 1918 virus more deadly than usual influenza?

A3: The virus caused a cytokine storm, an overreaction of the immune system that led to severe lung damage and respiratory failure, especially in healthy young adults.

Q4: How did World War I contribute to the pandemic’s spread?

A4: Large-scale troop movements, crowded military camps, and poor sanitary conditions facilitated rapid transmission across continents.

Q5: Were there any vaccines or effective treatments during the pandemic?

A5: No vaccines or antiviral treatments existed at the time. Medical care was limited to symptom relief and supportive care.

Q6: What public health measures helped control the pandemic?

A6: Quarantines, social distancing, school closures, bans on public gatherings, and mask-wearing were used with varying degrees of success.

Q7: Did the pandemic affect all populations equally?

A7: No. Indigenous and isolated communities often suffered higher mortality rates due to lack of immunity and limited healthcare access.

Q8: What lessons from 1918 are still relevant today?

A8: Early intervention, transparent communication, strong public health systems, investment in science, and global cooperation remain crucial for managing pandemics.

More Info: masterfxstrategies